Waiting for someone to die is a bit like waiting for a flight to depart after numerous delays. You know you’ll eventually reach your destination but you’re no longer wedded to a set date or time, having abandoned all faith in the estimated time of departure flashing brightly on the board above you. All you can do is linger in the interlude, shifting uncomfortably in plastic chairs and watching as other jets take off while you remain suspended. There's always that flicker of hope and relief with each new futile announcement, followed by the crushing weight of another postponement. Ultimately, the plane will depart when someone—or something—else beyond your control decides it's time.

As the process drags on you get increasingly frustrated, angry, even sad. You start asking questions like, “Why did that other flight take off? Why not mine?” and, of course, “How much fucking longer is this going to take?” You’re exhausted—depleted from waiting and strained with the unfairness of it all. You’re still connected with your point of departure but also halfway out the door knowing that the next location is imminent.

Perhaps there are people who can shrug off flight delays and, perhaps, those are the same people who can shrug off death and recite platitudes like, “It’s better this way.” I’m not one of those. I want to scream and dick punch the gate attendant while I shriek, “DO SOMETHING.”

The medical staff move about with practiced efficiency, like gate attendants following protocols. They check vitals instead of boarding passes, adjust morphine drips instead of seat assignments, wearing expressions that balance professionalism with feigned compassion. But neither can alter the flight path or final destination: they can only walk you through the process, handing out food and beverage certificates to make the wait more palatable.

The shitty pizza and trashy magazines help dull the anxiety. You may even forget about your predicament—what you’re really waiting for—for a few merciful moments. But then you’ll remember and your whole body will fill with that simultaneous understanding of longing for the inevitable and the maddening uncertainty of not knowing how or when relief will come.

Have you ever sat on someone’s death bed and watched for them to take their last breath? I have.

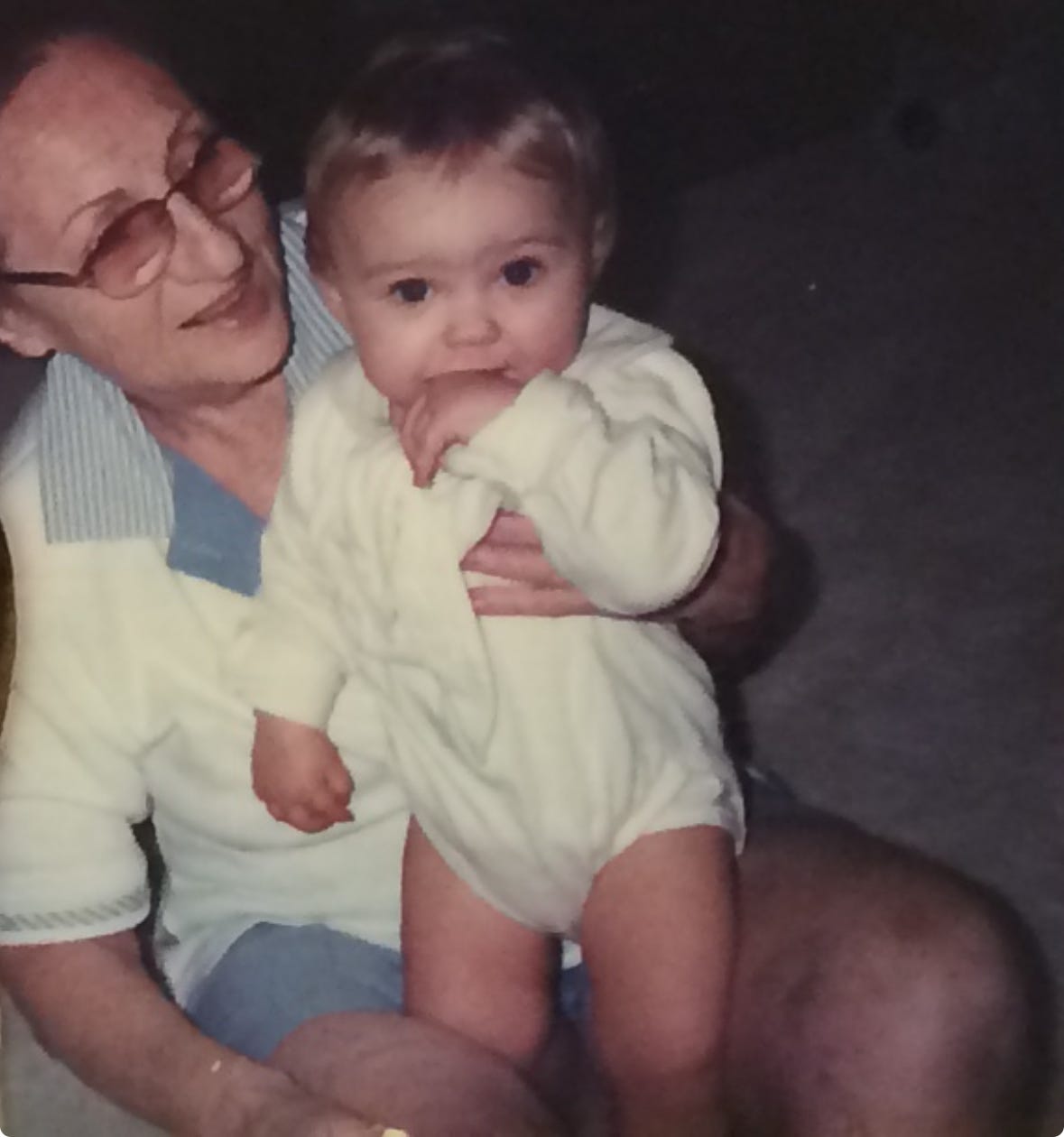

The first time I waited for someone to die was in 2018. My grandmother, a Holocaust survivor and all-around incontrovertible badass, called to say she was having dreams that forced her to relive the loss of her family to a bomb raid, nights sleeping in forests of countries far from home that she fled to on foot, and her days in the camps, transformed into a slave, when she was finally captured. By this point, she was well into her 90s and, simply put, over it.

I said that I understood but asked her to wait 24 hours so I could get on a plane to Fort Lauderdale—aptly referred to as “God’s waiting room” for this exact reason—to say goodbye. She promised me she would but I later learned that when my brother, already at her bedside, reminded her that I was en route to see her one last time, she deadpan replied, “Good, she can see me in a box.”

Despite her stubborn nonchalance and literal death wish, she kept her promise. She waited and I said goodbye. And then she waited some more. Days after I said goodbye, I returned to the hospice center with my dad and my Aunt E. My brother was walking through the lobby while my dad and his sister cackled regurgitating absurd stories about their life growing up in the Bronx—the characters they met and even became. They hadn’t gotten along in years—a sibling rivalry so deeply entrenched and riddled with resentment that it resulted in numerous prolonged periods of separation between the two.

I was sitting next to my grandma when my Aunt E announced, “She’s gone.” In the depths of my heart and even my logical brain, I truly believe she waited for her family to be together—reunited beyond their physicality—for her to take her last breath. You know what they say about death—it brings together the living.

Seven years later, almost to the week, I was flying back from Tokyo when I received a similar message, this time from my father, telling me that it was my Aunt E’s turn—that she was done and making her way to hospice. She no longer wanted to be a prisoner to the pain caused by her years-long battle with the cancer that had infiltrated and spread throughout her now frail body beyond the point of return.

I landed in Detroit and, once again, routed to Fort Lauderdale to say goodbye. I made my way to the airport lounge to wait out the hours until my new connecting flight. The kind-eyed bartender offered support in the form a glass of shitty red wine, which I guzzled before picking up the phone. I waited for my Aunt E’s face to appear on the screen. The woman who answered wasn’t my Aunt but some hollowed-out version of her I could barely recognize. I pleaded with her to wait for me as I choked on the salt in the tears that dripped onto my lap. Again, I would find out later that she had begged the doctors to end it days before my arrival but, in the end, like my grandmother, she waited.

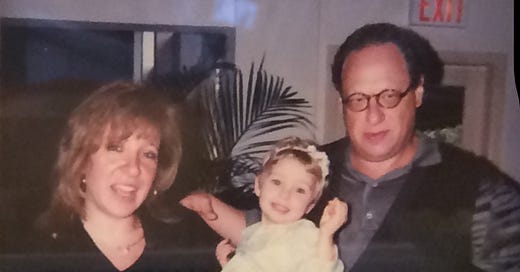

I spent the hours I had with her unable to keep my emotion in check. While my dad had been intermittently estranged from my aunt, I had grown closer to her, my grip on our bond tightening every time she told me she was proud of me without conditions or “buts”—something few people in my life did. Like my grandmother, she loved me without expectations and indulged my self-involved rants that I knew lacked perspective (and teeth), especially when I remembered that I was talking to true survivors.

I lay in her bed and told her on repeat that I loved her to which she would slowly whisper back the same words she had ended every phone call with for the last 31 years of my life: “I love you more, baby girl.”

Honestly, I prayed she would die while I was there. As she fidgeted in her gown, I could tell she was suffering—could feel that she was angry that the fight was over and that it wasn’t; that she had been forced to give up but the pain was being dragged out like some sort of cruel reward for having made it this far. Selfishly, I wanted her to stay, but I knew there was no coming back now, so I also needed her to go. For this to end. And I wanted to be the one holding her when it did.

As I write this, I’m still waiting for the call that her organs finally shut down and, in that truly metaphysical way, she can breathe again—somewhere better with my grandparents by her side.

And even though she’s not yet gone, the grieving process has been ongoing in parallel with her dying. Like her, I’m angry. I’m angry this happened to her. I’m angry that it was so painful for her. I’m angry that I didn’t get more time with her because I was a child used as a bargaining chip in a war between adults and because, as an adult myself, I simply failed to make the effort I should have.

In February, I cancelled a trip I had planned to fly down from New York with my babies to see her. I was exhausted and the thought of getting on a plane with two under three and a dog shortly after contracting norovirus was nauseating. Even knowing there was a possibility we could have infected her weakened system with that vile plague, I’m still sure that I’ll regret that decision forever along with every time I failed to make the drive north from my parent’s place in Sunny Isles to hers near Boca. I am mourning time lost in the past and time I could have had with her in the future. Leaving her bedside while she continued to breathe and maintain her wherewithal was one of the hardest things I have ever had to do.

Up until I received that text from my dad, I neither knew nor, I think, wanted to know, how sick she was. When I spoke to her two weeks prior to her hospice entry, the night before I left for Japan, she was in the hospital but sounded like herself: optimistic, laughing, smart. There was no mention of being out of treatment options or that someone had clicked fast-forward on the timeline truncating what I thought was years to days of her life.

I keep asking myself, “How?” I simply can’t wrap my head around how someone can transform from a seemingly normal version of their vibrant 70-year-old self into a skeletal shell of a being in a matter of days. How?

Most of the time, I’m angry because it’s less painful than the utterly desperate grief that has taken over my body—a cancer of its own sort, destined to plague the living. But, at times, I can’t help but let the sadness break through. I’m not only mourning the loss of someone I love wholly and deeply—whose laugh, wisdom and unwavering affection for me I will feel a void without in perpetuity—but I’m also mourning the fact that with her passing, I am losing what feels like the last remaining piece of my grandmother.

Despite my dad’s technical, genetic relationship with them both, for some inexplicable reason, he doesn’t quite feel like them. Somehow, my grandma and Aunt E always felt like a packaged deal, whether they liked it or not.

Of course, the imminent passing of my aunt also has me contemplating the deaths of my parents and in-laws. What lessons should I learn from this to avoid the should have, could have, would haves? How long will these lessons stay fresh enough in my mind so that I don’t start to ignore them and lean into habits I know I will later regret.

There are times where I feel ok. I tickle my daughter or kick a soccer ball to my son and I forget that she’s neither here with us nor somewhere watching over us as she told me she would be. My aunt is somewhere between life and death and I’m waiting with her: suspended between grief and mourning.